|

| My desk at work. |

Working and Writing for the Man. Full-Time System Admin, Part-Time Speculative Fantasy Author.

Thursday, June 3, 2021

Working Inside is Weird

Tuesday, May 4, 2021

Ode To a Shitty Burger

I like large burgers. I like sliders. I like pigs-in-blankets. I like hoagies. I like pulled pork sandwiches. I like ruebens, cubans, and breakfast sandwiches.

I like, really, anything with two slices of bread and a piece of meat in the center. It's primal and debasing to hold a burger and try to eat it as, like a collapsing star, it disintegrates into a slurry of deliciousness. Growing up, I would get a burger before getting my allergy shots for bee venom, convinced that the meat in my belly made me impervious to pain. What a ludicrous conclusion! But a serviceable salve to ease my fear of needles. Burgers were my answer to most of all life's problems when I was 6 years old. Today, they still kind of are.

Burgers, like friends, are fickle. Not all burgers are created equal. Some burgers disappoint and demoralize. Some even betray you. They illustrate the lie of consumerism and the commodification of once sacred and immutable things. Like a life of watching porn and encountering sex for the first time with another human being, eating a Carls Jr. Six Dollar Burger illuminates the hyperreality of bread, meat, cheese and vegetables advanced in the fictional ad space, while what is unwrapped in soggy wax paper is the cold truth: that all of us have been lied to. The burger today, indeed, does has a true referent, but it exists elsewhere, far from any motor oil encrusted strip-mall parking lot.

The shitty burger is the aesthetic product of many components. Down the street from my apartment, there is a decaying fast food chain, local to the Santa Barbara area. The reviews online are as abyssal and empty as the employees that absently attend the greasy kitchen griddle, and food poisoning is alleged all too frequently in that virtual space. The dinning room is always empty. Aging CRT televisions are void of light and sound. Vending machines contain stale baubles, forgotten behind scratched, hazy plastics. The employee that takes your order is tense and on edge. The fact that you are there in this solemn place is an act of violence. The order will most surely be incorrectly filled, but out of kindness you feign ignorance. The truth behind the shitty burger is the commiseration found in consuming it. The thin, dry patties are ingested under the wan light of a desk lamp in solitude and shame. In eating it, you have contributed to institutional racism and, simultaneously, are now emboldened to end it.

I would disagree with the post-modernists that we have lost the true referent, what I refer to as the proto-burger. Just like the desolation which attends the shitty burger, the proto-burger is a sum of harmonious parts. Just as the fresh cut tomatoes, the grilled onions, the chilled lettuce, and ground sirloin unify to achieve mythic synergy, so people also gather around charcoal grills on lazy Saturday afternoons to experience unshakable community. At the checkered picnic table, people of all kinds and creeds have the opportunity to experience the original and incorruptible authenticity of the proto-burger. And, like waking from a bad dream, the memory of the shitty burger fades, ultimately to nothing, thereby allowing only the knowledge of the proto-burger to endure.

Thursday, March 25, 2021

"Oncoming Traffic" By Stuart Warren

There was traffic on West 580, right in front of the Richmond-San Rafael Bridge.

Traffic rarely happens. When it does, it usually inspires fascination, even wonder. The passing traffic does not stop. Motorists spying in the moments between moments. Life oncoming, then gone.

This time was different though.

There were two cars hedged off to the right shoulder: a 2038 Tesla sedan and a 2018 Honda Civic. The rear crush points on the Tesla were pancaked—what remained of the trunk space, mostly gone. I glanced out of my window and saw the two drivers in a heated fight, a paramedic between them with her hands up. A police officer was dragging a dumbbell set—ejected from the trunk of the Civic—off the center lanes while we waited.

By 2028, most of the Bay Area was autonomous. By 2032, the rest of the state followed. The current Administration established a buy-out program for manual-pilot autos, encouraging the conversion. But, among the millions, a small minority held out. Mostly older men, and a younger generation galvanized by passionate rhetoric to retain their “right-to-drive.” When accidents happened, it always involved a manual-pilot car. There would be a highlight on the evening news—national coverage if the collision was big enough.

The Civic’s owner was red in the face with anger, spittle ejecting from her mouth. It wasn’t about the car. She stood her ground. This would be on camera, the pavement her stage. Ten-thousand talking heads explaining the nuance of car ownership, the “right-to-drive.”

It was something we debated at work, before our managers would step in to re-establish office etiquette. At church, I would argue the nuance of scripture, how the church adjusted for cultural changes, while others flatly denied my points, on the basis of free will and choice. In school districts some advocated—think of the children, they would say—for manual-pilot school busses, that it was unconscionable to entrust students to the cold will of the onboard intelligence.

But as passionate and antiquated the logic was, we all knew that 94% of auto-accidents involved manual-pilot vehicles. 100% of all autonomous cars were zero-emission, and manufactured by carbon neutral companies. Average commute time was lowered by 30% as the speed limit was raised by 25% across the western United States.

The police officer signaled to the line of stopped cars to proceed after a few minutes. I cracked open my book and thumbed to the page where I left off, feeling the pull of my body into the seat, the scene disappearing from view.

Where 580 merged with 101 North, brake lights crept up along

the frontage road.

Sunday, January 10, 2021

Respecting The Stillness

About the middle of the week during the so-called "protest" held at the Capitol building in Washington DC, I deleted Facebook and Twitter from my phone. It was just too much. The rest of the week's news was carefully filtered through messages delivered via Facebook messenger by writer, and fellow wookie life partner, Desmond White. They were mostly memes and updates about the ongoing certification of President-Elect Biden's win of the 2020 election. After all, humor disarms, and Desmond has enough of it to be awarded an honorary black belt in Judo.

It was quiet though, after the apps were gone. My mind was at peace. No notification dings. No wild Facebook threads of frantic, hateful people declaring their opinions. Pure silence. I had forgotten what that felt like. I grew up with it.

I was a part of the generation that first experienced common and widespread use of the internet. The internet that we know of today, at least. The kind with browsers and websites that shared videos and files. The kind that had Altavista for web searching and General Mayhem for whatever disgusting thing 4chan currently is. The "small device" didn't really exist yet. I didn't have a cell phone or iPod until I was in middle school. I didn't get my first iPhone until after I had graduated college (2012, maybe?), though, in all fairness, I had resisted getting one just because the carrier plans were so expensive. I'm sure there's no true correlation, but it was a little after getting the phone that I got my first major panic attack.

The idea of being constantly connected is both a blessing and a curse. I can't even express in words the convenience a cell phone affords when your car breaks down. During the pandemic, we can facetime with our parents and grandparents. Yeah, I know it's not ideal, but it's something at least! The increased distance we place between ourselves is problematic though. And there's a price to pay for being always connected. The speculative cyberpunk tv series, Ghost in the Shell: Stand Alone Complex, features an episode (S1E11) about a government-run, social welfare facility, where patients are treated for Cyberbrain Closed Shell Syndrome. TLDR, it's a sickness that afflicts those who can't break away from the internet and it's communities. Disconnecting a patient being treated for the sickness causes them to become violent, withdrawn, paranoid, depressed, comatose, or incapable of interacting with people for prolonged periods. Obviously the illness is creative hyperbole, with no true equivalent in the world. "Doomscrolling" and "shitposting" hardly compares, but the constant connection to Facebook and other social media websites already affects how we see the world and our attitudes towards others.

Now comes the weird part. How do I tweet/post/gram when I don't have these apps on my phone any more? Not very easily I guess... If I had to chose between my health and leveraging social media to tell people about my books, I'm obviously siding with the former. So, this will be an interesting next few weeks as I launch my third book and connect with people about it. Please be patient with me as I adjust.

Here's to a better, healthier 2021!

Sunday, December 13, 2020

Twofaced Politicians and Jarls and Bishops Only Want One Thing...

One of the things that I've struggled with when it comes to Christianity is it's sordid history when it comes to ecclesiastical structures. How could the common man come to know Jesus with all the elements seemingly against them? (Bad theology, no access to vernacular translations of the bible, endemic/systemic corruption, to name a few.) Because, if you are protestant, the implied answer is, "none." But that's a gross simplification and—arguably—blasphemous truncation of God's power to save and preserve his people, regardless of time period and reigning zeitgeist.

|

| A good example of the roman architecture being absorbed by the landscape. |

Recently I read an essay by Umberto Eco named "On the Shoulders of Giants" (coined from Bernard of Chartes's quote "We are dwarfs on the shoulders of giants.") Eco’s general thesis is that there is a productive tension between the past and present. Innovators spurn the past, invoking a "newer is better" philosophy, but willfully ignore the shoulders of the "giants" they stand upon (that is, the great thinkers of the past). I see this concept playfully imagined in Assassin’s Creed: Valhalla which presents a pseudo-historical recreation of Anglo-Saxon England, and the multicultural landscape of the time. The game itself, developed by Ubisoft Montreal, evokes the impression that it was heavily researched and painstakingly developed to render the world faithfully. Most impressive, is the haunting ruins that scatter the world map, which the developing nation-states occupy. Unlike Eco’s essay, the denizens of this medieval Britain, live in the shadows of giants, with their “modern” cities, parodies by comparison to the enduring roman infrastructure that are still serviceable some 800 years after their construction. Christianity is portrayed how I would expect it to be rendered in a AAA action rpg, though, to the game designer’s credit, the primary theological objective is to explore the mythology of Asgard and the eschatological conclusion of Ragnarök.

|

| One of the abbeys (I forget which) built around a roman aqueduct. |

All this to say, after the 77 hours I’ve put into this game so far, I realized that there was a striking resemblance between the bishops and jarls of Anglo-Saxon England and our modern politicians here in the United States, especially those that espouse a belief in Christianity. The development of Christianity, unfortunately coinciding with the fall of the Roman Empire, begat structures and organizational practices out of necessity, with ecclesiastical institutions filling the vacuum. Modern American conservatism lies to us and says that “things used to be better”, when the reality is less impressive: everything is still the same. People die and fuck and instigate conflict and oppress without pause, and will continue to until Jesus comes back. And, while, this might seem a trivial realization, I found it oddly comforting. If the televangelists and politicians of today equate to our previously mentioned bishops and jarls, then the typical, ordinary believer of today, likewise, existed.

Because of the well-designed

world presented by Valhalla, I can

reasonably imagine a man living in a hamlet beside a river, concerned with his

crops and animals. He takes a wife, has a few children, only one or two

surviving to adolescence. The village

is threatened on occasional by lawless

thugs or journeying Vikings. Otherwise, against this backdrop and the changing seasons,

the Church existed. People were forgiven and baptized, listened to the priest

and took communion, just like they did today. No one wrote books about their

unimpressive lives, whereas the conniving abbots and deceitful kings endured in

memory because their status in society afforded them biographers and notaries.

So, it’s comforting, in a weird way, I guess.

Thank you, Lord, that the world is boring.

|

| Urnes Stave Church: Built in 1129 in Norway. |

Saturday, October 31, 2020

Thoughts on The Witcher 3 And RPG Story-Telling In General

While I'm almost certain that others have documented this I was thinking about interactive storytelling in the context of playing video games, specifically western RPGs. (I have little experience with Japanese RPGs so I won't be covering that here.)

There's been examples of "choose your own journey" storytelling already in printed media. When I was a kid, R.L. Stine (of Goosebumps fame), introduced a new line of books called Give Yourself Goosebumps, where you could explore a book with branching plots. Generally you would read the book and then flip around the pages at certain points, guided by the spooky editor to continue the branching plot. The limitation of course is that the overall plot length was not very long, as far as total time spent reading. Honestly, I never read one to completion. I wasn't much of a reader until High School. However, I would see them all the time at my library when I was in elementary school, and flipping through them, enjoyed the concept more so than the content.

Similar to my love of reading, my love for western RPGs didn't bloom until high school as well. The first one I remember playing was Star Wars: Knights of the Old Republic, which had a variety of choices in game that would determine various future plot points. At the end of the game, you could even choose an "evil" or "good" ending! Likewise, Vampire: The Masquerade – Bloodlines also had branching storylines and alternate endings based off of decisions in game with various factions. (Still one of my favorites!) Of course, nowadays, games can have upwards of 20 different endings due to the level of resources made available by AAA studios. And this is where The Witcher 3 comes in to play. For those unaware of the franchise, The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt, is a western fantasy RPG developed by Polish game studio, CD Projekt Red. The game is based on the fantasy novel series of the same name, by Andrzej Sapkowski. The game takes place after the events of the books. Following a witcher named Geralt of Rivia, who is a tradesmen dealing in monster killing, royal body-guarding, and general mercenary work. For a general review of the game, see here.

Before I explain why I like The Witcher 3's general approach to storytelling, I should explain how most western RPGs depict their characters. Most feature protagonists that begin as blank slates with varying levels of cosmetic customization (from clothing to physical appearance). A smaller number feature fully developed characters that the player enters into to vicariously experience a narrative. (The Witcher 3 utilizes the latter model.) After this point, western RPGs will excel or flounder depending on the degree of immersion the simulated game environments generate. Most games can succeed if the character design and world design are adequate, but its the narrative pieces that string the player along for 60+ hours of gameplay.

Western RPGs simulate both standalone novels and serialized fiction because they capture multiple narratives contained in a greater world. A grand quest line can last up to 20 hours, simulating a novel, whereas one off requests and adventures serve as short fiction set in a larger conceptual world. Specifically, what I like about Geralt's character in The Witcher series, is that his life experiences accommodate the variety of in-game situations and dialogue choices that guide the progress of the game. Oftentimes, western RPGs feature a narrow subset of dialogue choices during play. These amount to A) good, B) bad, C) irreverent, and D) neutral. The intention of using these options is to give the character freedom to interact with the world and its characters, but they are arbitrary at best and functionally limited. Geralt's life experiences are varied enough that we can believe his responses to actions in-game. Not only that, but Geralt is an imperfect character, and his responses can vary between forgiving and capricious, with far reaching consequences for his actions. For example, Geralt has an opportunity at one point in the game to overthrow a nefarious king. The ability to do so is determined by whether or not Geralt assaults a non playable character several hours before the plot point opens up. And it's crushing to have the opportunity to end an evil king's reign, only to be stonewalled later on.

It's a weird thing to ponder the illusion of choice in games because it's all scripted ahead of time. But I like the concept of an interactive novel. It appeals to me as a greater form of storytelling, offering immersion that just isn't possible with conventional storytelling methods.

Tuesday, October 27, 2020

Talking with My Dad about Fact-Checking

|

| My dad and my brother at a BBQ back in 2013. |

The other day I was emailing my dad an article that The New York Times put out which fact checked the final presidential debate from this past week. My dad's response, was more or less what I expected:

The NY Times is long known to be a left of center publication. Hence their reporting reflects their acknowledged philosophic points of view. The Times “fact checkers" are only preaching to the choir. The “fact checkers” are hired by the Times. Would these folks opine contrary to the Times editorial board and expect to remain employed? Do you actually believe the Times would publish opinions that are not congruent with the established editorial opinions of the paper? It would be the similar if I sent you an article from the “Federalist” or from Fox News. Both data sources have an ax to grind.

My dad is very conservative, having been a devotee of Rush Limbaugh and Dr. James Dobson for most of his adult life, although the above was much softer than his usual assessment of the current political climate. What I found interesting was his position: the relationship between a paper's policy bias and its inherent "truthfulness" changes depending on the observer's own political alignment. Someone who is "liberal" would praise the Times for its desire to "uncover the truth;" whereas, someone who is "conservative" would cynically claim that the fact checkers were hired in bad faith. (I mention these in quotes to emphasize the relative absurdity each designation has attracted over the past few decades.) Of course, the reality is somewhere in the middling grayness. For instance, I would opine that most of what Fox News puts out on their network are news stories with an original spirit of truth, but filtered through a lens that confirms the biases of their viewership. The original story may actually be factual, but the interpretation detracts from the "truthfulness" of the presented story, to such a degree that the final result is no longer true. I think this goes the same for other news outlets on the left side of the isle, though to a lesser degree. In this instance, the final story still retains the original "truthfulness," but now is veneered with a layer of interpretation that deviates from the original meaning of the story.

To illustrate the ways this can happen, I have prepared an example meant to be an objective description (hypothetical of course) of events. (Remember though, true objectivity is impossible, regardless of viewpoint.)

Statement A)

Today, at 5pm, a protest occurred in downtown Los Angeles. Joe Smith, Professor of Black Studies at UCLA, organized the event to bring awareness to a recent event where Black suspects were detained and suffered injuries. After 2 hours, a fight broke out between protestors and counter-protestors. The police were called in response leading to the arrests of 3 protestors and 2 counter-protestors.

Typically, journalism reports the above and adds subsequent commentary to interpret the event. So a Fox News newscaster may include additional commentary on top of Statement A to create an entirely new Statement B:

Statement B)

Today, at 5pm, a student protest occurred in downtown Los Angeles. Joe Smith, Professor of Black Studies at UCLA, organized the event to bring awareness to a recent event where Black suspects were detained after resisting arrest and suffered injuries. After 2 hours of what local business owners described as complete chaos, a fight broke out between protestors and counter-protestors wearing MAGA campaign clothing. The police were called in response leading to the arrests of 3 protestors and 2 injured counter-protestors.

The above adds additional descriptive information that, while technically true, distorts the original meaning of the information. The addition of "student" will delegitimize the protestors as being politically immature. The addition of "after resisting arrest" justifies the injuries sustained to the detained men. The addition of color commentary from eyewitnesses charges the event with subjective emotional energy. The addition of "wearing MAGA campaign clothing" assumes that the protestors were agents of anarchy, whereas the counter-protestors were supporting a return to order by the current Executive administration. The final addition of "injured" insinuates that the protestors were violent and the counter protestors were not.

The same kind of additions can be added for a left leaning message:

Statement C:

Today, at 5pm, a protest occurred in downtown Los Angeles at Bunker Hill. Joe Smith, Pulitzer Prize winning professor of Black Studies at UCLA, organized the event to bring awareness to a recent event where Black suspects were unlawfully detained and suffered injuries. After 2 hours of peaceful demonstrations, a fight broke out between protestors and armed counter-protestors. The police were called in response leading to the arrests of 3 protestors and 2 counter-protestors charged with intimidation and brandishing a deadly weapon.

The additional details highlight the location of the protests taking place in a cultural center of downtown Los Angeles. The organizer, Joe Smith, is given credibility with his past achievements. Adding that the suspects were "unlawfully" detained suggests systemic injustice in some form contributed to the circumstances surrounding the arrest. The quality of the demonstrations as "peaceful," gives sympathy to the protestors, who are threatened with violence by "armed" counter-protestors. The final detail of the 2 counter-protestors being "charged with intimidation and brandishing a deadly weapon" further indemnifies the actions of the original protestors.

So, yeah, subjective statements are fucked up.

Given the above, we have only looked at statements, and how objective data can be modified with commentary to create a subjective message. But this kind of influencing can go to additional lengths to influence the subconscious of the subscriber. The curating of related and unrelated stories in a segmentation of news media can add an additional "metastory" on top of everything that then further tints the overall interpretation of all events in the given time frame. Depending on the publication's perceived audience, the metastory will adhere to a particular philosophy, the objective to confirm the bias of the readership. Late author and semioticist, Umberto Eco describes this in his satirical novel Numero Zero, which analyzes the underlying methodology of tabloid media (which in this case, concerns the various regional conflicts and cultural eccentricities of Italy in the early nineties):

"I know it's commonly said that if a labourer attacks a fellow worker, then the newspapers say where he comes from if he's a southerner but not if he comes from the north. Alright, that's racism. But imagine a page on which a laborer from Cuneo, etc. etc., a pensioner from Mestre kills his wife, a newsagent from Bologna commits suicide, a builder from Genoa signs a bogus cheque. What interest is that to readers in the areas where these people were born? Whereas if we are talking about a laborer from Calabria, A pensioners from Matera, a newsagent from Foggia and a builder from Palermo, then it creates concern about criminals coming up from the south, and this makes news..." pg. 46-47

So the idea Eco summarizes (from the point of view of Simei, the Editor-in-Chief of the fictional magazine, Domani) is that, if a newspaper advocates for a specific philosophy, there are ways to use objective data to make a subjective meta-statement that will guide the reader to a specific conclusion. For instance, Fox News might report three of the following (hypothetical) stories in a 24 hour news cycle:

- "Obama congratulates Hillary Clinton on her new book in a Facebook post."

- "Clinton Foundation fired an employee for [unspecified] misconduct."

- "Wikileaks obtains emails involving a large investment made by Hillary Clinton in a German technology firm."

- [Indicates a close association (professional and personal) between Hillary Clinton and Barak Obama.]

- [The Clinton Foundation is corrupt.]

- [Hillary Clinton is beholden to foreign interests.]

|

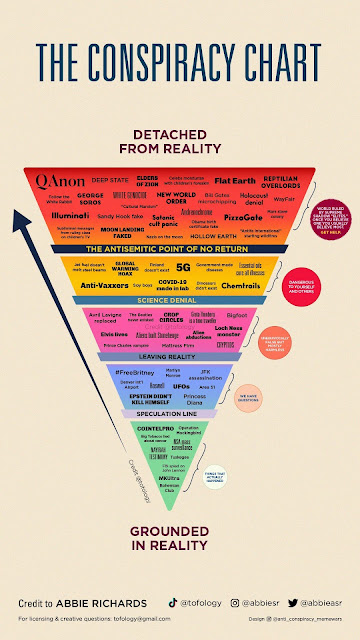

| I highly recommend looking at Abbie's research into conspiracy theories and how they develop |