|

Working and Writing for the Man. Full-Time System Admin, Part-Time Speculative Fantasy Author.

Monday, April 1, 2024

The Theology of Star Trek

Friday, February 16, 2024

The Unexpected Theology of Vivienne Medrano's Hazbin Hotel

There’s occasions where I watch something and it moves me

enough to think about it in excess. Hazbin Hotel is one

such show.

The general conceit of the show is one of a deep desire to be redeemed out of habitual sin. It begins following the aftermath of a yearly purge (a la The Purge film franchise) wherein the angelic host of heaven descends into a Dantean like Hell to cull the population of demons that have begun to overcrowd the region. (Fantasy notwithstanding, I was already interested with the idea from a theological perspective, wondering if this was some form of delayed annihilationism.) Charlie Morningstar, the daughter Lucifer Morningstar (Aka Satan), having witnessed this for the umpteenth time, is moved to action and decides to establish a halfway house for sinners desiring salvation. And, of course, there’s lots of singing.

What I found really remarkable about the show, developed by Vivienne Medrano, was

the honesty and authenticity of the characters. In the same vein as her

previous YouTube series, Helluva

Boss—despite what I, a white, Christian male may think about the character’s

choices or actions—there is something inherently magnetic about Charlie’s

altruism, Vaggie’s cynicism, Angel Dust’s deviance, and Husk’s standoffishness.

They are real and relatable, which, honestly, is the true objective of any kind

of creative writing, and the result is fantastic. And while the overtly crass

language is unrealistic and distracts from what can be transpiring in the

episodes, the overall substance underneath I found compelling.

Theologically speaking, the writers of the show ask very

thoughtful questions about the nature of life, or justice, of forgiveness. For

instance, in episode 2, when Sir Pentious (essentially cobra commander anthropomorphized

as a full sized cobra in steampunk attire) is caught in the act of trying to sabotage

the hotel, Charlie encourages him to ask forgiveness. In the musical number

that ensues she says “… it starts with ‘sorry.’ That’s your foot in the door.

One simple ‘sorry’… The path to forgiveness is a twisting trail of hearts, but ‘sorry’

is where it starts.” Even when Vaggie (Charlie’s girlfriend) and Angel Dust,

indicate that they would rather succumb to their desire to just kill Sir

Pentious, Charlie insists, “but who hasn’t been in his shoes?” It’s easy to

dismiss the show as “satanic” and “depraved” as conservative critics are

undoubtedly saying, but as we are all made in the image and likeness of God, our

deep inner propensity to want forgiveness and salvation is startlingly on

display throughout the show.

In a subsequent episode, “Masquerade,” Angel Dust’s sexual abuse

is discussed, where it’s implied that, despite being proud of his overtly erotic

disposition, the life that he has been sold into is demeaning and exploitative.

Like many of the unknown actresses and actors that work in the adult film

industry, His only recourse is to forget his trauma through heavy substance

abuse. Although the musical exposition between himself and Husk seems to

undercut the same need to reform that Sir Pentious expresses earlier, their conclusion

is still something remarkable: that they are damaged and exploited people that

need each other to get by in a brutal and desperate world.

My favorite episode, “Welcome to Heaven” was by far the most theologically developed. Charlie and Vaggie are allowed passage in to Heaven to argue their case in an angelic court as to whether a soul can be redeemed out of Hell. When asked what the criterion is for salvation, Adam (of Genesis 3 fame) rather ineptly suggests that it’s to, “act selfless, don’t steal, [and] stick it to the man.” When Angel Dust demonstrates these moral acts mere moments after, it begs the question: what actually earns a soul a trip to heaven? The assumption that it is by some formula of good deeds and virtuous living that allows a soul to migrate to Heaven after death is nothing new. We seem to naturally justify—or wish to justify—that what we do matters. I think that this is because our mortality compels us to make a mark on this world so that our memory outlives us. I myself want to write books, to be incorporated into the cannon of Western Literature. But we are taught by both the Bible and recorded history that this aspiration is the height of folly. The list of famous and well to do figures, forgotten by the passage of time must be staggeringly large, just as 99.9% of all the species that have gone before us are now extinct. That Hazbin Hotel seizes on this ambiguity regarding the requirements to go to heaven, is remarkable, if only because it encourages discussion around the worthiness of Christ’s life, death, and resurrection, and why something like it would distinguish itself so much from the competing ideologies around justification. It just makes me happy that people who may, or may not, know God have come so far and has expressed a desire to try something different.

Of course, this isn’t a show about Jesus, or why we should be compelled to accept his grace and forgiveness. The cosmology of Heaven and Hell is all wrong. The motivation behind why someone may take part in heaven, or willingly chose hell, isn’t accurately described. The hierarchy of demons, sourced from the Lesser Key of Solomon (based on the Testament of Solomon), is not sourced from the canonical books of the bible, but from dubious extra biblical sources that cannot be reliably dated. And yet, those who wrote the show and brought it to life, are people with dignity and respect, being made in the image and likeness of God. Even though I may not agree with the conclusions, the questions asked are valid and demand a response.

I think it behooves us as Christians and non-Christians to dialogue

about these kinds of things more frequently, and it encourages me that someone like

Medrano could voice them so creatively and compellingly. I would highly

recommend a watch. Be advised however, and understand, that this is certainly

not Veggie Tales, but a show about very real people who are closer to the Kingdom

of God than they realize.

Tuesday, February 6, 2024

More Thoughts on Warren Ellis

Back in 2020 I found out that Warren Ellis had committed acts of sexual coercion, according to the testimony of several women he had known in his past. Much to his credit, he did come to terms with the women he had had relationships with, mostly facilitated through this website which was launched in 2020. Through a truth-and-reconciliation styled open dialogue, it appears that Ellis was able to sort it all out, although for many I imagine it's hard to forgive and move on.

Since then, I continued to purchase used hardcovers and trades of Ellis' work, secretly hoping for his eventual absolution. (Thankfully, that seems to have happened, generally, in the court of public opinion.) And what I've found is a consistent narrative trend in his work that elevates characters of varying ethnic and cultural backgrounds. While the counter-cultures of LGBTQAI+, Anarchists, Marxists, Punk (Steampunk, Cyberpunk, Raypunk, et al), and others have existed in some niche form or another, I am confident that Ellis involved himself in those circles long before "it was cool" to do so. Of course, I realize that this is suspiciously the equivalent of the "I'm-not-racist-because-I-have-a-black-friend" argument, but credit where credit's due.

I think I enjoy Ellis' style mostly for it's playfulness.

There are other writers out there that are very good at this, like Tom King and Patrick Rothfuss. Even Umberto Eco, on occasion, would have some really funny repartee going on between characters in the midst of a long debate about medieval philosophy. Levity in conversation is its own reward, but when the discussion is high and elevated, the shift in tone is a good reminder that, at the end of the day, we are just reading a story somewhere while the real heroes are out saving lives and making sure our transit systems don't derail (figuratively and literally). Ellis exceeds all expectation when he is doing this. For example, Ignition City features this exchange:

And most of his books feature numerous instances of this.

In general, he strikes me as someone who has "done the reading," so to speak, when it comes to various topics. For example, in FreakAngels, Ellis frequently discusses aspects of engineering and technology at work in a flooded post-apocalyptic London, such as renewable power generation and rooftop greenhouse farming. While I'm mostly certain that he is not a trained scientist and engineer, the ideas he leverages are based on real ideas and theories. It never seems like technobabble, that is.

My only gripe with Ellis is his audacity to start a very good story and ultimately never finish it. Ignition City, Trees, and Injection are both such examples. He also has a tendency to abruptly end stories, which can be traumatizing (in the most hyperbolic sense). However, to his credit, he was able to finish Castlevania, which ended rather wholesomely, despite the breadth of material covered in the show. His novel, Gun Machine also had a rather satisfying ending.

On a whole, despite his past, my appreciation for his unique brand of storytelling has increased. He's consistent and delivers on a regular basis: the dream of all writers and readers.

Monday, December 20, 2021

An Object of Scorn

Affixed to the altar before the apse was the cross. It’s edges were frayed, roughly hewn from quarter sawn timber long ago. The reclaimed piece was swollen and pocked with burls. Striations of discoloration, wrapping around the trunk, intimated the shape of a hobbled man, or a rot in the wood. Well-lit by the clerestory above the chancel, the cross was positioned prominently, as if basking. The carpenter had placed the cross there, shunting it into a notch in the ground, embroidered with mosaic tile. He cursed the splinters collected by his hands.

Over time, the basilica changed many hands, each flock with their own vice and preference. For a century or so, the cross absorbed bitterness and contention. In-fighting broke out across the aisles, until a meeting was convened to determine the spirit of their creed and what they said about their Lord. Most were satisfied by the outcome. At the end of it, the rich young ruler who ordered the meeting stepped forward and placed a thoughtful hand upon the hardened exterior, sensing great things ahead.

Not soon after, it was stained with blood. Buckets of coagulated sanguine absorbed into the sword-gouged trunk, bright red, before fading to purple and blue. Suffering abounded in the lands choked with smoke and ash, until a pragmatic flock emerged, resourceful enough to stifle the sickness of violence that seemed to infect the sullen, stagnant air. The cross was crowned with temporal power by the rich young ruler, but the gilded crown bore the likeness of a bad forgery.

New edicts were established regarding what the cross could and could not be. It took the aspect of many things. The cross was showered with wealth and abundance. Even the soft gold coins withered the cross’ face, bruising and softening the wood. Two attendants fought over the cross, for a time, until they conceded, finally, to a stalemate. Each mutually regarded one another with hate, their flocks diverging. They sat apart from one another, on either end of the cross. It stood between the camps, buffeted by anger and distain. After a time, the flocks relented, weary of the conflict, abandoning the refuse of entrails and sinew they had draped over the arms of the cross. The dawning light, emerging through the open portal in the narthex, exposed the rot. And members of both flocks returned to clean it as best they could.

The cross still stands there now, black as charcoal and steeped with dried blood. Some still approach, as if recognizing an old friend. Those that stay, marvel for a time and consider the carpenter that left it so many years ago. Those that depart, do so quickly, though not before dressing it in fashionable clothing, berating it, and covering it with semen and feces. The weight of shackles, handcuffs, bandoliers, braids of Ethernet cable, fascist flags dipped in gasoline, drape around its neck like a noose. There, on the altar, it stands: objectified by filth, defeated.

Yet, despite all this, the flock heaps their burdens upon it willingly. And they depart, each one, with a spring in their step.

Tuesday, October 27, 2020

Talking with My Dad about Fact-Checking

|

| My dad and my brother at a BBQ back in 2013. |

The other day I was emailing my dad an article that The New York Times put out which fact checked the final presidential debate from this past week. My dad's response, was more or less what I expected:

The NY Times is long known to be a left of center publication. Hence their reporting reflects their acknowledged philosophic points of view. The Times “fact checkers" are only preaching to the choir. The “fact checkers” are hired by the Times. Would these folks opine contrary to the Times editorial board and expect to remain employed? Do you actually believe the Times would publish opinions that are not congruent with the established editorial opinions of the paper? It would be the similar if I sent you an article from the “Federalist” or from Fox News. Both data sources have an ax to grind.

My dad is very conservative, having been a devotee of Rush Limbaugh and Dr. James Dobson for most of his adult life, although the above was much softer than his usual assessment of the current political climate. What I found interesting was his position: the relationship between a paper's policy bias and its inherent "truthfulness" changes depending on the observer's own political alignment. Someone who is "liberal" would praise the Times for its desire to "uncover the truth;" whereas, someone who is "conservative" would cynically claim that the fact checkers were hired in bad faith. (I mention these in quotes to emphasize the relative absurdity each designation has attracted over the past few decades.) Of course, the reality is somewhere in the middling grayness. For instance, I would opine that most of what Fox News puts out on their network are news stories with an original spirit of truth, but filtered through a lens that confirms the biases of their viewership. The original story may actually be factual, but the interpretation detracts from the "truthfulness" of the presented story, to such a degree that the final result is no longer true. I think this goes the same for other news outlets on the left side of the isle, though to a lesser degree. In this instance, the final story still retains the original "truthfulness," but now is veneered with a layer of interpretation that deviates from the original meaning of the story.

To illustrate the ways this can happen, I have prepared an example meant to be an objective description (hypothetical of course) of events. (Remember though, true objectivity is impossible, regardless of viewpoint.)

Statement A)

Today, at 5pm, a protest occurred in downtown Los Angeles. Joe Smith, Professor of Black Studies at UCLA, organized the event to bring awareness to a recent event where Black suspects were detained and suffered injuries. After 2 hours, a fight broke out between protestors and counter-protestors. The police were called in response leading to the arrests of 3 protestors and 2 counter-protestors.

Typically, journalism reports the above and adds subsequent commentary to interpret the event. So a Fox News newscaster may include additional commentary on top of Statement A to create an entirely new Statement B:

Statement B)

Today, at 5pm, a student protest occurred in downtown Los Angeles. Joe Smith, Professor of Black Studies at UCLA, organized the event to bring awareness to a recent event where Black suspects were detained after resisting arrest and suffered injuries. After 2 hours of what local business owners described as complete chaos, a fight broke out between protestors and counter-protestors wearing MAGA campaign clothing. The police were called in response leading to the arrests of 3 protestors and 2 injured counter-protestors.

The above adds additional descriptive information that, while technically true, distorts the original meaning of the information. The addition of "student" will delegitimize the protestors as being politically immature. The addition of "after resisting arrest" justifies the injuries sustained to the detained men. The addition of color commentary from eyewitnesses charges the event with subjective emotional energy. The addition of "wearing MAGA campaign clothing" assumes that the protestors were agents of anarchy, whereas the counter-protestors were supporting a return to order by the current Executive administration. The final addition of "injured" insinuates that the protestors were violent and the counter protestors were not.

The same kind of additions can be added for a left leaning message:

Statement C:

Today, at 5pm, a protest occurred in downtown Los Angeles at Bunker Hill. Joe Smith, Pulitzer Prize winning professor of Black Studies at UCLA, organized the event to bring awareness to a recent event where Black suspects were unlawfully detained and suffered injuries. After 2 hours of peaceful demonstrations, a fight broke out between protestors and armed counter-protestors. The police were called in response leading to the arrests of 3 protestors and 2 counter-protestors charged with intimidation and brandishing a deadly weapon.

The additional details highlight the location of the protests taking place in a cultural center of downtown Los Angeles. The organizer, Joe Smith, is given credibility with his past achievements. Adding that the suspects were "unlawfully" detained suggests systemic injustice in some form contributed to the circumstances surrounding the arrest. The quality of the demonstrations as "peaceful," gives sympathy to the protestors, who are threatened with violence by "armed" counter-protestors. The final detail of the 2 counter-protestors being "charged with intimidation and brandishing a deadly weapon" further indemnifies the actions of the original protestors.

So, yeah, subjective statements are fucked up.

Given the above, we have only looked at statements, and how objective data can be modified with commentary to create a subjective message. But this kind of influencing can go to additional lengths to influence the subconscious of the subscriber. The curating of related and unrelated stories in a segmentation of news media can add an additional "metastory" on top of everything that then further tints the overall interpretation of all events in the given time frame. Depending on the publication's perceived audience, the metastory will adhere to a particular philosophy, the objective to confirm the bias of the readership. Late author and semioticist, Umberto Eco describes this in his satirical novel Numero Zero, which analyzes the underlying methodology of tabloid media (which in this case, concerns the various regional conflicts and cultural eccentricities of Italy in the early nineties):

"I know it's commonly said that if a labourer attacks a fellow worker, then the newspapers say where he comes from if he's a southerner but not if he comes from the north. Alright, that's racism. But imagine a page on which a laborer from Cuneo, etc. etc., a pensioner from Mestre kills his wife, a newsagent from Bologna commits suicide, a builder from Genoa signs a bogus cheque. What interest is that to readers in the areas where these people were born? Whereas if we are talking about a laborer from Calabria, A pensioners from Matera, a newsagent from Foggia and a builder from Palermo, then it creates concern about criminals coming up from the south, and this makes news..." pg. 46-47

So the idea Eco summarizes (from the point of view of Simei, the Editor-in-Chief of the fictional magazine, Domani) is that, if a newspaper advocates for a specific philosophy, there are ways to use objective data to make a subjective meta-statement that will guide the reader to a specific conclusion. For instance, Fox News might report three of the following (hypothetical) stories in a 24 hour news cycle:

- "Obama congratulates Hillary Clinton on her new book in a Facebook post."

- "Clinton Foundation fired an employee for [unspecified] misconduct."

- "Wikileaks obtains emails involving a large investment made by Hillary Clinton in a German technology firm."

- [Indicates a close association (professional and personal) between Hillary Clinton and Barak Obama.]

- [The Clinton Foundation is corrupt.]

- [Hillary Clinton is beholden to foreign interests.]

|

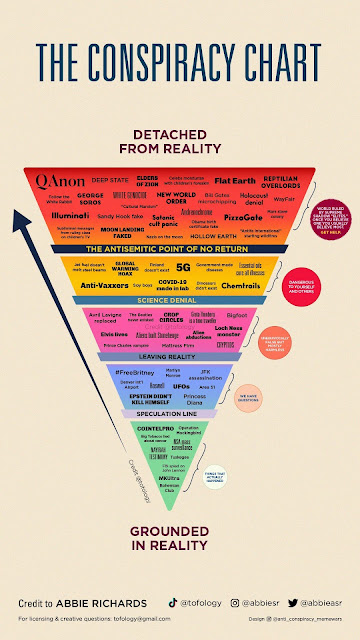

| I highly recommend looking at Abbie's research into conspiracy theories and how they develop |

Sunday, May 24, 2020

Why It's Better To Share, Instead of Borrow

Holy shit! Is it my birthday? I thought. Guy Pearce is my jam! So of course I embarked on a binge of this very short miniseries. (3 episodes, 3 hours)

I was impressed. Before I tell you why, consider the following.

Every so-and-so has done the Christmas Carol story before. Despite the story being of English origin and set in the very specific context of industrialized England, somehow Americans has also been hooked. This is likely due to the biblical overtones of the story. The three ghosts can loosely represent Christocentric ideas like the Trinity or the three days Jesus spent in the tomb after his crucifixion. The story of redemption, of forcing a man to repent for his sins and receive salvation. The lessons taught about generosity, grace, and the worship of material wealth. Even Scrooge's first name, "Ebenezer," is derived from the Hebrew word "ebhen hā-ʽezer" (literally "stone of help"), to symbolize the divine assistance Scrooge receives from the spirits, as well as the heart of stone Scrooge possess until his redemption. It's all there and easily received by a population that is loosely familiar with biblical verbiage.

The story is so ubiquitous (over here, "across the pond") that I grew up on several iterations of Dicken's work including, but not limited to, Mickey's Christmas Carol, The Muppet Christmas Carol, Scrooged, and A Christmas Carol, featuring George C. Scott (1984). (While jogging my memory, I discovered a version with Patrick Stewart!? What have I been doing with my life?) And, even if some of these versions are unfamiliar, it's likely that at least one of these has made it into your life at some point.

|

| I actually liked Scrooged the best growing up, seeing it as some kind of Ghostbusters spin-off. |

So, yes, I was very impressed with the recent version put on my FX. The expanded format allowed for a greater level of narrative depth in areas previously unexplored, such as the politics of the afterlife and the hellish bells that toll there. There is also motivation on Marley to move Scrooge to repentance. For, if Marley fails, he will be cast into an unrelenting purgatory. The #metoo movement is invoked when Scrooge forces Mrs. Cratchit to undress in front of him so that she can take out a loan for live-saving surgery for her son Tim. The spendthrift policies of industrialized Britain and the deadly cost of unbridled capitalism are as relevant today as it was then (corporate loopholes, poor working conditions, the wage gap, the working poor, unaccountable executive, etc.). There is even a scene depicting the rationing of coal, where Cratchit is, absurdly, charged for having additional coals provided to his stove in Scrooge's office. Each of these details cement the viewer in the time period and add layers of complexity to the story that has too often been sanitized by an over-emphasis on joyful climax. (Yes, Scrooge is redeemed. But that doesn't negate the pain and neglect he caused, or the inevitable restitution implied by his change of heart.)

But why write about this in the summer? Why is this important?

I actually was hooked by a line read by Pearce in the show, and I knew that I would want to write about it eventually, but never had the time to do so. Specifically, Pearce states the following:

"A gift is but a debt, unwritten but implied."This idea got my attention, as I languished on my mom's couch last Christmas. Specifically, I had bought my brother a 3D printer, which I wanted to give as both a celebration of his personal industry and the accommodations he made for me while we visited our father in Hawaii. It was quite an expense, something only made possible by money recently bequeathed to me from my late grandmother, but it was worth it. The above quote seemed to explain something behind the materialistic motivations inherent in gift giving. Though my brother was none-the-wiser, there was some part of me that that sought recompense.

|

| Guy Pearce as Scrooge. |

I've always been fascinated by the interaction of words, specifically when people use different terms interchangeably. The language behind share and borrow is markedly different, despite their everyday use as equivalents. Both terms invoke the collaborative ownership of something (wealth, property, resources, etc). Both are primarily positive in connotation. Where the terms part ways involved the object of the sharing or borrowing, In the latter case, borrowing implies that resources gained are returned. Sharing implies extended or perpetual ownership. I would not be the first person to write about the implications behind gift giving. But what I seem to get stuck on is the liquidity of the terms.

Sharing reminds me of the early Christian Church. In the Book of Acts 2:42-47 we read the following:

42 And they devoted themselves to the apostles' teaching and the fellowship, to the breaking of bread and the prayers. 43 And awe came upon every soul, and many wonders and signs were being done through the apostles. 44 And all who believed were together and had all things in common. 45 And they were selling their possessions and belongings and distributing the proceeds to all, as any had need. 46 And day by day, attending the temple together and breaking bread in their homes, they received their food with glad and generous hearts, 47 praising God and having favor with all the people. And the Lord added to their number day by day those who were being saved.

The only reason I bring the bible in to this, is because Americans typically leverage biblical language, the language of A Christmas Carol, while championing the acquisition of wealth, equating divine favor and moral excellence to those who were most adept. But, clearly, in the bible we see a different idea taking place: the sharing of resources for the betterment of the collective. This is essentially a prototype of communism, where members of the community own the "means of production."

|

| Oldie, but a goodie. |

Scrooge's statement, where a gift demands reciprocity in some form, brings an argument against charity, that in giving there is an implicit motive to justify one's self. Or, we simply give to feel congratulated and compensate for a moral failing that looms over our consciousness. The moral of A Christmas Carol promotes the idea of selfless giving, specifically grace.

Borrowing, as a concept at least, implies temporary ownership. It is active on the part of the supplicant, passive on the part of the provider. One goes to an institution and asks for a resource and is given that resource, with the understanding that this resource will be repaid in some capacity over time. Obviously this practice is monetized to favor the institution. Some form of additional reciprocity is sought to justify the initial lending. This is typically done with charging interest, where a percent of the total money left to be repaid is charged in addition to the principal. I'm laboring on the minutiae of this to prove a point: of the two terms, only borrowing is inherently predatory.

When we share our resources, we are committing to mutual prosperity and strength. A community, even on the fringe, will survive indefinitely when operating under the concept of sharing resources. Likewise, when someone buys "shares" in a company, they are participating in a group effort to see something come into being. Sharing, in my mind, aligns with the concept of grace; that is, unmerited favor. Grace is a gift. There is no implied debt or language hinting at future reimbursement. It flies in the very face of modern theories like laissez-faire capitalism, where economies are advanced on the basis of self-interest and competition over limited resources. This is incompatible with the Gospel and the concept of sharing. But, even Christians seem consigned to rationalize the use of free market capitalism as a means to an end, or a necessary evil that we must all endure for the sake of general order. Verily, Jesus never said, "Blessed are the poor, that is, unless they deserve to be poor because they collect food stamps, make bad decisions, and are addicted to meth." Sharing involves two active participants, and, rather than the supplicant approaching the provider, it is the provider that approaches the supplicant.

At the end of the day, the nuance of this argument can be obfuscated by quick tempers and personal narratives. Objectivity flies out of the window and we typically keep to our camps, where the firelight is warm, comforting, and calming. Rarely are we forced to venture beyond the borders and confront the wilderness. That would require bravery, after all. I know that my philosophy is influenced by the teachings of Jesus, which some may find hostile for tertiary reasons. If you, reader, are not a fan of the whole Christianity thing, then consider something like the Utopian future of Star Trek, embodied by the fictional organization known as the United Federation of Planets. In this speculative timeline, resources are shared within the federation. Though there is money exchanged between the Federation and other species (ie, the Ferengi, who covet "gold plated Latinum"), the act of doing so is implicitly denigrating to both parties. And, though it seems absurd to live life based on fictional principals, just because it's not real doesn't mean it can't have an impact on how experience the world and interact with it. (In my case, I believe Jesus is reality, which I would call a "win" in my book.)

Anyways, that's what's been on my mind the past few weeks.

In other news, I finished my 3rd book this weekend. I am beyond excited to share the details with you as the book enters the design process!

#TheWorkingAuthor

Wednesday, May 8, 2019

Imagine a Hat...

Keep in mind, this could be all completely wrong. But it makes sense to me.

Maybe this comes from what I've seen in film and stage plays. Hamlet holding a skull, contemplating death. Sherlock Holmes with a magnifying glass, snooping around. The T-800 wearing black leather and a pair of menacing sunglasses at all hours of the night. All this makes sense to me, especially when writing a character that is outgoing, socially adept, or professional. These kinds of characters smoke cigarettes, drink whiskey, dance on poles (light, stripper, or otherwise), wear white gloves or black hats, and hold on to things while they walk. Visually, these brief descriptions invoke certain archetypes in literature and film. You can imagine the symbol of a cowboy being made up of the sum of his/her parts: wearing a white/brown/black hat, smoking Marlboro, and drinking coarsely ground coffee that's been watered down to make it last longer. But even the associations between cowboy and cigarette conjure, in my mind at least, a rogue desperado walking up a steep incline toward a crest that overlooks a parched desert valley.

Internal characters, developed vis a vis a method actor perspective, are much harder to write. In my case, characters written in first person-limited essentially demand that I get inside their heads, which is challenging. It's so easy to influence the decisions made by the characters first of all. The author is biased in different and fundamental ways. If the character is a drug addict, the authenticity lent by the author is, at best, representative and not autobiographical. (That is, unless, the author is Hunter S. Thompson.) To get inside the head of a drug addict requires extensive research and interviews with those involved in that kind of lifestyle. The creative act therefore is not solely rooted in literary devices and diction, but in how pieces of evidence are knit together into a cohesive collage that, over time, becomes a homunculus made of pixels or bleached wood pulp (depending on the preferred medium of the reader). So, in essence, the method-actor-author is like a serial killer, flaying his/her victims and stitching together the pieces into ghoulish abominations. (I'm pretty sure that's what happens in True Crime novels at least.)

At this point... I'm stuck somewhere in between the two, which is amusing because of how black-and-white I often think about things. My characters typically drink whiskey, or throw rocks across ponds, or shave in the mirror, but I also read Godel Escher Bach and I am a Strange Loop to better understand the mathematical philosophy behind artificial intelligence and how that can be used to theorize how neurons relay information through our brains. I guess there is merit for each perspective.

As Alyssa works through draft two of my second novel, it's good to consider these things so that I have some better angles on the third and final draft.

Saturday, April 13, 2019

Philosophy and Shit

>

>

Enraged, curious, stimulated by what you just read?! Comment below! Let's talk about it!

Sunday, February 3, 2019

The Process (Of Writing a Book)

The above are only screenshots of a large document. By the time the book is finished, this document balloons in size. But I can’t even say how many times this document has saved my ass and helped Alyssa track all of my thoughts.

Monday, November 12, 2018

The Funny Thing About Names

Tuesday, July 17, 2018

The Memes of Racism

|

| One of the original instances of Pepe. |

What got me thinking about memes yesterday was the hijacking of one such meme, “Pepe the frog” and its use by neo-Nazis and white nationalists (AKA the Alt-Right).

|

| Iterations of the Swastica used in Eastern cultures. |

A famous example of a neutral symbol being commandeered for hate is the Swastika, which originated in a host of Eurasian religious traditions. In Hinduism, the symbol was associated with luck and general wellbeing. While the origins of why the Nazis took this symbol escape me, I want to say that it had something to do with the belief that India was once known as a seat of a powerfully advanced race of Caucasians, but don’t quote me on that. Anyways, regardless of the origin of the Nazi belief, the symbol was taken and used as a hate symbol. Also, the image of the cross of Christ’s crucifixion has also been co-opted by White supremacists and the KKK by using it to intimidate African Americans by burning them on their lawns, or public places. I think it’s interesting then that people have taken Pepe, something so ephemeral in the grand scheme of things, and created a hate symbol out of him.

|

| A cross burning, carried out by the KKK. |

Monday, June 25, 2018

Inventing Enemies

- Eco states that enemies are first geographically different than us. They come from the outside. He cites the barbarians invading Rome at the peak and decline of the Roman Empire as chief examples. In today’s terms someone can be an “enemy” of ours if they reside in another country. We may never have met these people, or have had any long distance contact (i.e. wireless communication, internet chatting, etc), but they are someone removed from us. And their distance makes them the easiest target for creating an enemy for us to fight/oppose.

- Likewise, another degree of separation occurs with language. Eco cites the same example of the “barbarian” languages that invaded Rome, weakening the national identity of Rome. The word barbarian suggests a corruption of language (bar-bar-ian, like a stutter in speech). Those that we can’t understand, which requires us to have contact with them either personally or via audio message, we would reject as people we are against.

- After language comes those that live inside the city walls. Those that are strange to us are most likely to be immigrants. The United States has a long history of targeting immigrants, either 1st or 2nd generation, that have come from foreign lands to be with us and are at the beginning, or in process, of assimilation into the parent culture. These are people that are ESL (English as a Second Language) or they work less desirable jobs or they are having trouble finding a footing in a strange and new environment. They are easy to pick out in a crowd, maybe because their clothing is different, or because they live in ghettos where other fellow immigrants reside. We often make enemies of these people because they are easy to blame for things that are seemingly outside of our control. Crime, population density, government spending, and education burdens can all be easily blamed on the “immigrant” by the interior culture.

- Eco suggests, after his studying of Medieval history and philosophy, that those suffering from deformities would be the deepest layer where we could make our enemies. Assuming that the person on the outside has come in, learned our language, adopted our culture, and has demonstrably become essential to the community, those that are missing limbs, blind, mentally impaired, or suffering from congenital defects are seen as enemies because they lack on a fundamental level core abilities of other humans. This may not be as much an issue today as it was a thousand years ago, but an equivalent can be found in the homeless, who are dehumanized for their inability to care for themselves. They are seen as feral, unstable, and incomplete, therefore becoming an adequate enemy. Eco seems to have the most sympathy on this level of inhumanity simply because individuals of this strata are the easiest to blame and have few advocates.